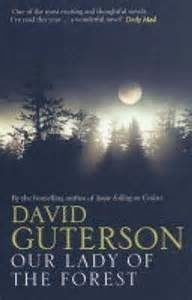

Review of Our Lady of the Forest, by David Guterson

Review of Our Lady of the Forest, by David Guterson

My usual pattern upon finishing a book worth reviewing is to let it simmer in my mind for a few days before embarking on the review. I find that my impressions after letting it settle are not the same as those when I reach “The End.”

I’m a fan of David Guterson, and I read it with attention to craftsmanship, because in many respects he writes with a style I’d like to emulate in my own works, and sometimes with similar choice of themes, as in Our Lady of the Forest. I rate this book highly, in the grand scheme of things, but on the Guterson-scale, disappointing. I care deeply about the themes he was addressing, here, and I was looking for him as a master craftsman to handle them deftly. He came through on that score, and yet I am disappointed. Disappointed that he wrestles mightily with the biggest of questions, and loses.

Guterson understands the competing worldviews, and he understands well the gut-level human needs that are the context in which these worldviews are maintained and grappled with. So he can be forgiven, for example, making fun of the Catholic vision-followers in their over-eager religious tourism. Similarly the pasty and confused young priest. It serves a sub-theme of the book, that religious practice often deflects us from truth-seeking, rather than serving it. If the claims for which the priest’s religion stands are true, then so much that is done in the name of that religion are stuff and nonsense.

I read avidly in hopes that the book would get us to the conclusion that through all this vision-mongering we would see genuine but pathetic attempts to find the God who is, rather than only the conclusion of Carolyn, the mouthy self-indulgent hanger-on who teaches us that it’s all illusion for rubes and hayseeds.

In places we get a hint this will end badly, as here:

Most of the pilgrims … were moved to consider their mortality by the forest’s sea-green cathedral light. The trees rose like pillars. Out of the fallen trees grew new trees. A delirious photosynthetic rapture suffused the air of the place. There was so much evidence of decay and birth it was discomfiting and comforting at once. How could this be here and people matter very much?

Hm. Missed a word. The word “Not.” How could this be here and people NOT matter very much? Guterson was defeated by the argument from evil, the devil’s tried and trusty fall-back. It appeals if we lack the imagination to try to adopt God’s perspective. It’s not the presence of evil that needs to be explained. It’s the presence of good.

I know I’m giving a thumbs-down in part because I don’t like Guterson’s metaphysics, rather than his treatment of them. But in addition, the last 5,000 words or so of this novel was a let-down. After deftly touring the competing ways of thinking, with quite memorable characters conveying human truth, we’re given the answer to all this awful struggle and silliness of mankind, instead of the ambiguous, wondering question. A master craftsman wrote 90% of this book, and then a ham-handed apprentice took over.