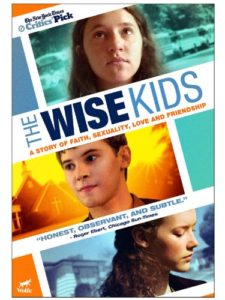

The Wise Kids is a 2011 film that for some reason is just now starting to gain traction. It’s probably a sleeper because it’s artsy and think-y. Probably also because the two-line blurb for the movie is, as usual with Netflix, remarkably inept.

The Wise Kids is a 2011 film that for some reason is just now starting to gain traction. It’s probably a sleeper because it’s artsy and think-y. Probably also because the two-line blurb for the movie is, as usual with Netflix, remarkably inept.

First Things contributor Eve Tushnet did a good write-up on the movie here. A major theme is loss of faith, but many will watch the same movie and decide that the more significant element is sensitive and even-handed consideration of those looking across the divide between evangelical Christianity, and homosexuality as a lifestyle.

Three friends are seniors in Charleston, South Carolina, about to graduate and go off to college. Tim, Brea, and Laura are heavily involved in their church group. The movie begins with them preparing for an Easter play. If you have at any time had a connection with Evangelical churches, and especially Baptist churches, and especially such churches in the South, and especially the youth group(s) in such churches, you will instantly recognize this milieu, and likely find it cringe-inducing. You might even think that this is a not-so-subtle set-up for a devastating slam on fakey self-righteousness enclosed within false humility, all in service to a triumphalist-tinged brand of plastic religious practice.

It’s not. Hang in there.

Brea is presented as the main character and she suffers a loss of faith. It is sudden, in her case. We’re given to understand that it comes as a result of considering for the first time the possibility that there are people actively in opposition to the claims of Christianity, as opposed to merely not being thus far receptive to the good news. Acting upon this, she googles some sites on supposed Bible contradictions, and learns that there are accounts of some elements of Christianity in other religions, such as virgin birth, crucifixion, and resurrection. She steps back from her computer, breathing deeply.

Brea is presented as the main character and she suffers a loss of faith. It is sudden, in her case. We’re given to understand that it comes as a result of considering for the first time the possibility that there are people actively in opposition to the claims of Christianity, as opposed to merely not being thus far receptive to the good news. Acting upon this, she googles some sites on supposed Bible contradictions, and learns that there are accounts of some elements of Christianity in other religions, such as virgin birth, crucifixion, and resurrection. She steps back from her computer, breathing deeply.

Let’s pause the movie for a moment, and consider her reaction. Granted that cinematic interest requires a quick pacing through the process—we don’t have to read the internet with her to understand what she’s thinking in real time. But suppose this were a more deliberative process. It’s worthwhile to look at the claims of inconsistency. For someone reasonably well grounded in history, open to differing ways of thinking, and conscious of the difficulty of communicating an infinite God to finite people, the claims seem childish. But they’re not to be simply avoided. Likewise, virgin birth legends and dying god scenarios should be considered for what they are, instead of having them catch someone like Brea unawares, instantly throwing into question the uniqueness—and therefore the validity, in her mind—of the Gospel presented by Christianity.

If you’re a Christian watching this movie, and one who is somewhat weathered by the spurious false voices out there, you might feel like jumping out of your chair to explain to poor Brea that of course it’s not so simple as she thought. Time to grow up. Time to consider that there are all kinds of alternative voices and counterfeit voices vying for your attention. We are not re-made by Christ to quail at the first hint of challenge. Brea should dive deeper. Find out what’s going on. Research it. Seek the truth. You may want to counsel Brea to remember that the truth, paraphrasing Spurgeon, is like a lion. It doesn’t need to be defended. Release it and let it defend itself.

Brea’s faith is a hothouse flower, however, unable to survive upon being transplanted into the wild. She folds like a pup tent in a strong wind, never recovering from this one mild but–in her case–fatal blow to the beliefs she cherished until five minutes ago. If you’re not a believer, you may applaud her as the beautiful and kind heroine who also finds reason and escapes the self-imposed restraints of religion. If you are a believer, you may experience anguish that she trades what is solid and real and true, for worldliness that is ephemeral, transient, and false. And that, on such flimsy evidence.

The counterpoise to Brea’s way of thinking is Laura’s, a character who by the way is magnificently acted by Allison Torem. Laura is quite conscious of the challenges to faith, but she knows it’s true; she feels it. She begs her friend Brea not to throw off her faith “lightly.” She chafes at the manifold compromises around her but does so in love, as best she can. She struggles, but does not lose sight of the guiding star truth. If you are a believer, you will hopefully want to be like her. If you’re not a believer, you will likely find her character nonetheless compelling, in favor of uncompromised followers of Christ.

The counterpoise to Brea’s way of thinking is Laura’s, a character who by the way is magnificently acted by Allison Torem. Laura is quite conscious of the challenges to faith, but she knows it’s true; she feels it. She begs her friend Brea not to throw off her faith “lightly.” She chafes at the manifold compromises around her but does so in love, as best she can. She struggles, but does not lose sight of the guiding star truth. If you are a believer, you will hopefully want to be like her. If you’re not a believer, you will likely find her character nonetheless compelling, in favor of uncompromised followers of Christ.

Then there is Tim. While Brea rejects faith and Laura clings to the solidity of God’s written revelation, Tim carries on seemingly without serious concern that his self-identification as gay should pose a serious challenge to his faith. He believes, unlike Brea, but you have to ask about his understanding of God. What does this God require of us? Is the Bible true, or not? Tim is unconcerned. “Let’s do this,” he says of the nativity scene in which he is to play a part. He proceeds confidently in the face of unbridgeable inconsistency.

Then there is Tim. While Brea rejects faith and Laura clings to the solidity of God’s written revelation, Tim carries on seemingly without serious concern that his self-identification as gay should pose a serious challenge to his faith. He believes, unlike Brea, but you have to ask about his understanding of God. What does this God require of us? Is the Bible true, or not? Tim is unconcerned. “Let’s do this,” he says of the nativity scene in which he is to play a part. He proceeds confidently in the face of unbridgeable inconsistency.

Tim “comes out” to his friends Brea and Laura early in the film. His announcement is a catalyst to the crises of faith which follow. Certainly it must contribute to Brea’s doubts. It explains in part Laura’s opposing response: not to synthesize this new bit of data into her belief system, as Tim does, but instead to reject it as inconsistent.

It has to be said that the movie contains sensitive portrayals of evangelicals through the eyes of gays, and of gays through the eyes of evangelicals. A curious plot development in the film involves Cheryl, an atheist Brea befriends. In a night-club scene near the end of the movie, Cheryl is attracted to another woman. What are we to make of this? That the divide between theist and atheist coincides with the divide between straight and gay? Had the Cheryl character been straight, the movie would have made a good bit more sense. The nightclub scene mars the picture.

It has to be said that the movie contains sensitive portrayals of evangelicals through the eyes of gays, and of gays through the eyes of evangelicals. A curious plot development in the film involves Cheryl, an atheist Brea befriends. In a night-club scene near the end of the movie, Cheryl is attracted to another woman. What are we to make of this? That the divide between theist and atheist coincides with the divide between straight and gay? Had the Cheryl character been straight, the movie would have made a good bit more sense. The nightclub scene mars the picture.

But that’s a quibble. This is an excellent film, forget the Netflix rating. See it. Recommend it to every Christian you know. Make it a subject of conversation at church. Most importantly, think of your children and of the next generation as being like Brea and Tim, leaves blowing in the wind, perilously close to being detached from the truth.

Very Good film. I watched it twice and have been discussing with another about it. I agree with most things you say about it. What you get from the film certainly depends on your outlook, weather theistic or not but it did reveal a certain forced culture. I pulled from the movie a lot of “implication”, like the father that reads about the universe suggesting that he has an interest in science that some think might be a contradiction to some of his beliefs as perceived by the community that he’s trying to stay a part of. Also, when Brea was evaluating her position, they showed her do a quick internet search but I really think that just began a 9 month journey for her which would involve much more reading and asking the questions like when she met with the unbeliever in her room and asked her “what do you think happens when we die”. The movie didn’t have time, probably, to really go into how much she may have looked at it. Very good movie!

Also, it was interesting how certain ‘arguments” were hit upon subtly giving reason for some to pause in the epistemology,,, is our pathway to what we think is true reliable. “do you think we would believe something different if our parents taught us something else”, asked Brea to Tim, who responded, “I think I would” giving a somewhat nervous laugh after saying it.

Oops, I should have said, “is our pathway to the actual truth reliable”.. not what we think..

I hear what you’re saying about Brea possibly being engaged in a longer search than what the movie suggests. There are subtle hints along the way during her senior year that she’s struggling. Whether it’s over a 9 month period or sudden, my point about it is that Brea is caught up short, “unawares,” as I wrote in the review. What concerns me about it is that at age 17 or 18, growing up in an ostensibly Christian household and being a regular attender at church, she ought to have been better prepared. I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately, your comment is timely for me. It’s distressing to me that churches are so bad about preparing people. Even the churches that are good about going deep in theology are usually bad about presenting the alternative metaphysical propositions, the ones that people run into as soon as they sift through what the culture is deceitfully presenting as the truth. It is all too common that they fall into doubt and then disbelief simply because they’re unprepared for alternative claims to truth. That’s a travesty, imho. In church they’re often fed this cotton-candy version of Christianity that seems intent on keeping them in perpetual childhood, clinging to a mythical ozzie-and-harriet, Disneyworld version of Christianity that does not really exist and never did. Instead, they should be getting the whole grisly story, not the sterilized empty version, and set on a path of truth, like the catechumens of old, first identifying and then denouncing the false gods, spitting and cursing in their direction, and then turning, literally, to face the east, the direction of resurrection and hope. To me the relevant time period is not the zero to 9 months it might have taken Brea to lose her faith, but the 18 years preceding it. For some reason we Christians (in America, anyway) are all about being embraced by our Friend, but insist on ignoring the Enemy. This whitebread, be-nice, wimpy version of Christianity sets us up to be strangled by the indefensible atheist materialism lurking beneath the pretty wrapping of culture. And as usual, we sacrifice our children first.

I recognize you’re looking at this from the other side, I’m not attacking you, I’m giving you my perspective. I suppose your view of the movie would be that it well represents the kind of slow awakening to an alternative version of truth than that presented by Christian teaching (such as it is). Thus, with the movie’s very subtle allusion to science, you see (because it’s through Brea’s eyes, in that instance) that the doubter is aware that scientists often set themselves up as prophets of a version of reality in opposition to Christianity. But to me that’s exactly the kind of shallowness that makes me crazy. Science is not in opposition to Christianity. In fact, I think history bears the conclusion that Christianity sponsored science, in the sense that its understanding of the natural world (in contrast to pagan and other belief systems previously) uniquely enables the practice of science as we now know it. Moreover, science should never be considered in opposition to Christianity because it is by definition only the study of the natural world. If your field of study is exclusively geology, you don’t conclude from that that the earth is all there is! And so for Brea to observe her pastor father reading science, and for us the audience to conclude that he is a doubter, is trivial and silly, but the movie is not trivial and silly, in fact it’s genius because it’s accurately pointing out that this trivial and silly way of thinking moves us, as it moves Brea.

Thanks for your thoughtful comment.

Ouch….my thinking doesn’t feel trivial or silly.

You might have misunderstood. I was commenting on the movie’s visual of the science book and Brea’s noticing it, and what we the viewer are supposed to infer from her looking at the science book. I think it’s trivial and silly that anyone would set science and Christianity in direct opposition, as if each was the opposite of the other. It’s like saying apples are the “opposite” of oranges. It’s disturbing too that this whole false opposition would be inferred just from the quick glance Brea had at her pastor father’s science book. I read science all the time, but it doesn’t cause me to doubt my faith (quite the contrary, in fact). I tend to want to criticize the movie for setting up that visual with the expectation that all this bogus science vs. Christianity inference would attach, but I can’t, really, because it’s not a far-fetched expectation, unfortunately.