The Privative Thesis

Christopher Hitchens wrote of atheism that “our belief is unbelief.” A.C. Grayling wrote that atheism was merely a “privative thesis,” by which he meant that it is nothing more than the subtraction of supernatural reality from one’s conception of all of reality. This is a common point of view: belief in “nothing.”

But it’s nonsense.

If we subtract the supernatural from our conception of reality, it doesn’t leave us believing in “nothing.” It leaves us with affirmative beliefs such as: that matter comes from true nothing and self-develops into ever more complex matter; that we encounter the physical world without the aid of the supernatural imprinted into our consciousness; and that material self-development explains our hard-wired and shared orientation to the good, the true, and the beautiful. These beliefs are assuredly not belief in “nothing.” The atheist point of view is not a “privative thesis.”

Faith

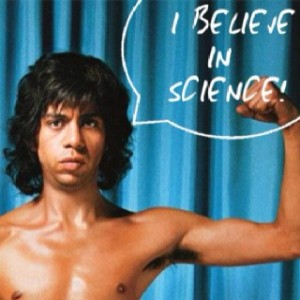

Most atheists don’t say their entire worldview is one of unbelief. Instead, they reserve this void in their belief system only for God. About materialism, they’re believers. They may say, like Esqueleto, “I believe in science.” Now belief in “science” makes no sense, but belief that ultimate reality consists only in that which is empirically verifiable does. That’s what is really meant by “belief in science.”

Most atheists don’t say their entire worldview is one of unbelief. Instead, they reserve this void in their belief system only for God. About materialism, they’re believers. They may say, like Esqueleto, “I believe in science.” Now belief in “science” makes no sense, but belief that ultimate reality consists only in that which is empirically verifiable does. That’s what is really meant by “belief in science.”

And that is faith. “Faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen,” as Hebrews 11:1 tells us. Matt Emerson points out in a piece for the Wall Street Journal that this definition for faith applies just as well for the enterprise of science, as when scientists patiently waited for confirmation of Einstein’s gravitational wave theory. The truth of that theory was the thing hoped for and for which they had conviction of truth. That truth was “unseen” until recently confirmed, 100 years later.

As Mr. Emerson pointed out,

The fundamental choice is not whether humans will have faith, but rather what the objects of their faith will be, and how far and into what dimensions this faith will extend.

Just so. Scientists are no more rational than religious believers, and may be less so. Religious hopes and convictions are as rooted in evidence as those of science. It is simply false to assert, as some loud atheists do, that faith is belief without evidence. Atheists disbelieve the evidence for God, but that is not mere disbelief. That is necessarily an affirmative belief that all of reality is explainable entirely through material causes. Atheists have to be saying, for example, that the universe is self-created; not just that no God created it.

Complacent Agnosticism

An agnostic might effectively fall into the same trap of faulty reasoning as do atheists, declaring himself neutral on the basis of what he doesn’t believe. But agnostics don’t really believe in “nothing,” either. An agnostic may decide not to weigh the evidence on this question of God, and thus avoid it. Or he may decide that it is unknowable absent some gnostic, experiential, interior, knowing on the question, and so avoid it on that basis. He may conclude that avoidance of the question about ultimate reality is a rational position to take.

But this just amounts to staking out a position that doesn’t exist — a false neutrality. In the name of taking no position, the agnostic takes a position. The agnostic is actually adopting a belief in a kind of nothing-as-such — avoidance itself is the substantive belief on the central question of God’s existence, and remaining beliefs about reality are consequently drawn from the zeitgeist, not reason.

This phenomenon of complacent agnosticism can be abetted by a misguided desire for freedom. We want to live with no constraints. We may find doctrines of belief to be constraining, especially if they have implications for how we live. We may then desire to reject them all, so as to have complete freedom for ourselves. The mistake is that all doctrines of belief are not thus rejected. Only the inconvenient ones are. Those that remain may not even be rationally coherent.

I believe in everything. Theists suggest there is more then that. That which we cannot see but only imagine in our human desire for an eternal existance and immortality. Isn’t every thing enough? If theism is true, would we want more when we get there? Will that not be enough?

That’s clever. By “everything” you mean every material thing, not really everything. You mean the cosmos, earth, people. You don’t mean ideals of the good, or the true, or the beautiful, and you certainly don’t mean God. You then ask, about those material things, “isn’t ‘everything’ enough?” Well, if ‘everything’ means everything, then yes. But if “everything” means only what you have relegated it to mean, then no.

But to your next point. If theism is true, would we want more “when we get there?” I assume you mean heaven. A Christian concept; not necessarily a theist concept, but I’m trying to work with you here. I think you’re asking whether heaven will be enough to satisfy us, and you’re suggesting that it won’t be; that we’re always reaching for that something beyond.

You’re doubling down on the metaphor. You’re suggesting that if what we experience here is a pale reflection of what we will experience in the great by-and-by, then maybe what we experience there will be but a pale reflection of something beyond that, and so on. Well that seems like a stretch, pardner. We hear echoes of something here that makes us think of something beyond, no doubt. But there’s no reason to suppose that it infinitely reflects, like those facing mirrors at the barber shop.

But I like what you’re doing with this. The important thing is that you’re not denying the echoes here of a reality elsewhere. You’re suggesting that the echoes even of that elsewhere are echoes of a reality of somewhere else, yet again. If that’s what you’re doing, you’re on the path to a reincarnated existence and a constant recycle. But that’s still theism. That’s not a path of atheism.

Excellent comments and reply.

“Nothing comes from nothing,” one of the few verities unwittingly uttered by King Lear of the eponymous tragedy. Truly the atheist gets nothing from his insistence on an absence of belief as a liberation.

Agnosticism as avoidance resonates for me because I have yet to meet an agnostic with a sense of urgency to match the importance of Gods existence and what that means for humanity. They have always seemed rather lackadaisical.

Also, Like the faith parallel to the verification to Einstein’s gravitational wave theory. Will read WSJ too.

Thanks

The existence of faith in the pursuit of science is helpful. One of the most irritating (and false) tropes of the new atheists is the idea that faith is belief in something when there is no evidence for it. That is not true for religious belief and it’s not true for science, and both for the same reason.

Agnosticism is deeply puzzling to me and I have been trying to unravel it. I think the absence of urgency stems from the false belief that rejection of claims of religion equates to belief in “nothing,” which is why this site is full of discussion of what nothing is and isn’t. On this point, incidentally, I think you’ll especially appreciate the posts on Agora and Running in Place.