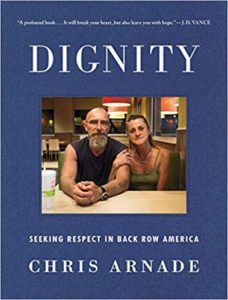

I read a bunch of reviews of Chris Arnade’s recent book Dignity before picking it up myself and they often remark upon the objective and nonjudgmental approach Arnade takes. He’s purposely encountering people we might think of as down and out, to try to understand them. One of his conclusions is that a major driver for all of them is a desire for dignity. Another, I think, is they’re all people inherently deserving of respect as such, even if the way they’ve lived their lives renders them invisible, or perhaps ignore-able, to the rest of us. The book is not about loss of dignity from financial hardship only, but rather about diminished human dignity more generally. It is an invitation to take a second look at the marginalized people in our midst and reconsider our relationship to them.

I read a bunch of reviews of Chris Arnade’s recent book Dignity before picking it up myself and they often remark upon the objective and nonjudgmental approach Arnade takes. He’s purposely encountering people we might think of as down and out, to try to understand them. One of his conclusions is that a major driver for all of them is a desire for dignity. Another, I think, is they’re all people inherently deserving of respect as such, even if the way they’ve lived their lives renders them invisible, or perhaps ignore-able, to the rest of us. The book is not about loss of dignity from financial hardship only, but rather about diminished human dignity more generally. It is an invitation to take a second look at the marginalized people in our midst and reconsider our relationship to them.

I found I had a rising sense of unease about how Arnade might think we ought to respond. Perhaps we’re being led to conclude we should remove any standards of sobriety, decorum, sanitation, and basic consideration for others, because to have standards is to be judgmental, which is to distance those without standards from us, which is to deprive them of dignity. He’s not explicitly asking us to empower the government to force us to make up their financial or competence lack, and anyway how does one mandate respect? But by looking into the lives of people we might ordinarily pass on by, we might be led to cast about for the easy fix, and end up with destructive socialist policies.

We also might conclude that the path to greater dignity for others is to turn our focus inward, so to speak, to reduce person-to-person barriers within ourselves, since we can’t do anything about the self-imposed psychological barriers of those others, including those we recognize as being marginalized. This might take the form of zealous acceptance without conditions. Acceptance is a central theme of Arnade’s book – how the absence of it motivates people. People don’t go to the non-profits for help, for example, instead they go to McDonald’s (where people like this tend to congregate, evidently) where no one places conditions or implies expectations. They are accepted. People do drugs because (among a lot of other reasons, I’m sure) among other drug users they are always accepted; there are no standards of behavior required for admittance. Psychological barriers to entry to church are minimal, too, I was gratified to read, especially in hole-in-the-wall churches composed of ex-addicts and formerly marginalized people themselves.

If it were possible, would it be an unqualified good that we accept everyone around us, unconditionally and with no expectation of any standards? If you ignore or avoid me because I’m a criminal or dangerous or a beggar or a bigot, you don’t “accept” me, but should you, really? There is a two-way street here. If you accept me despite those defects of character, doesn’t that diminish my reason for avoiding defects of character? If I have power over women and exploit them, and you accept me anyway, then why change? Suppose I’m an addict and prostitute and I don’t try to work honest jobs. Accept me anyway? How is that helping me? My moral failure is the problem, not your lack of acceptance. You should want to see me cured of my moral failings, not navel-gaze your own false guilt. You’re not to “judge” me in the sense of counting yourself as my moral better before God, but neither are you to set aside your own discernment between good and evil.

Seems to me. The book is very good on this point, however: that people on the margins do not – because they cannot – place their hope for meaning in material things or really, by any economic measure. So they derive meaning from alternative sources, Arnade says, including “grace, place, and faith,” all of which are increasingly denied them in a materialistic world. This is a valuable point, and I think he’s right about this. It ought to make us look at what’s going on and realize that those who thrive economically may nonetheless be unwittingly trapped in the poverty of materialism. Here I mean “materialism” in both senses. One, as a synonym for naturalism; repudiation of the supernatural. Two, a drive for acquisitiveness that pushes aside virtues other than diligence and self-control and independence, with the result that we outsource meaning to our consumer choices.

We can allow pursuit of material gain to be our sole value and our sole measure of dignity. If that is taken away from us, we might actually be better off. People on the margins don’t look to that, they look to other things: “grace, place, and faith.” The marginalized people won’t find dignity in materialistic pursuits. They reach for it with other kinds of pursuits. A certain kind of aesthetic, for example. Arnade cites pigeon-keeping, which is a sort of art form, really. This is what he means by “grace.” Also place, such as when the people of decrepit Cairo hang on because they have a sense of self-identity which is associated with the town rather than with economic opportunity elsewhere. And of course religious faith, which to my mind ought to be the ultimate source of dignity, wherein we find identification with Christ and therefore ultimate meaning for our existence.